Materiality isn’t something you should think about once a year.

Well done on clicking the link and getting this far! Let’s face it; it’s hard to get excited about the issue of materiality. If your job requires you to read about it, you will know that most articles on the topic won’t really teach you anything new, let alone help you understand anything at all. But here you are anyway, checking this one, hoping it will be different.

It’s incredible how much work has gone into this topic over the years with dozens of reports, methodologies, guidance and definitions used. Let me put that another way: no one has a definitive answer. But to be fair, it does depend on who is asking the question.

The premise of non-financial reporting is not about ticking boxes: it is about setting a proper internal policy to manage risks and opportunities associated with the material issues which matter most to your company. The way you report on this is secondary. Nonetheless, it sometimes appears that it is the process of reporting that drives the materiality assessment.

Reporting does matter. It is your chance to tell your staff, shareholders, customers and other relevant stakeholders that you understand you need more than a P&L to judge your company’s performance. To understand what these issues include, you will need to consider the main non-financial concerns your stakeholders have about your company. Subject to your internal processes and/or any regulatory requirements, there is a lot of leeway in the approach you can take.

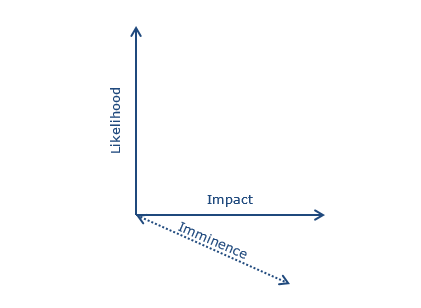

It is quite common to apply a materiality matrix to differentiate the level of impact and likelihood for each risk. Often these material issues are then scattered as dots across an XY plot at the start of CSR reports.

In the worst cases, these risks are inconsistent with the ones listed in companies’ mainstream financial reports, so it is useful to make sure you are using your company’s methodology to assess risks before reporting on them publically. With the new non-financial reporting requirements across the EU, there is increasing focus on these silly mistakes, as we see in the reports that WBCSD and others produce.

An unintended consequence of a materiality XY plot can be over-emphasising the distance between each point of the plot, rather than the actual purpose of the materiality assessment - i.e. to help inform and prioritise the appropriate mitigation strategy to reduce the likelihood and severity of a set of risks.

Something is missing. The matrix and XY plots are only in two dimensions. They ignore a key factor in business management and planning: time.

Adding a third axis to account for the imminence of the impact and its likelihood makes an issue jump from obscurity to something you ought to get a handle on in the current financial year and business plan. As a result, you can prioritise your material issues in a way than can be actioned within the next business cycle.

But how do you define time is not as arbitrary as it might seem.

On a planetary scale, a “long time” could mean tens of thousands of years. From the perspective of a CEO, a “long time” could be ten years. Many of the headline CSR policies we hear in the corporate world have been driven by CEOs’ personalities. Like government ministers, their time horizon extends only as far as their tenure.

While you might argue that large institutional investors, such as sovereign wealth or pension funds, are interested in long-term return, they are subject to the same turnover of management and governance.

Every new management team will have its own outlook and priorities, with the result that a company’s headline CSR policy can be quietly retired with its departing CEO. The dedicated CSR teams left behind can be expected to soldier on for a few years without any top-level cover. However, these teams will likely disintegrate as a result of corporate restructuring, budget cuts and disillusioned staff moving on. If a new CEO doesn’t come on board, isn’t pressured to invest in CSR, or isn’t won over by the CSR team within 5 years, then the policy and influence of the previous leader will expire. They won’t be delivering anything other than minor contributions to annual reports.

From a company’s perspective, the lifetime of a CSR policy and the timeframe of the material issues it seeks to address, should be set at 5 years. Short term should be defined as the current or next financial year, while long term should refer to anything past 5 years; beyond the horizon of an average CEO’s tenure. There are two reasons why this is important.

First, while you may have identified climate change as a long-term risk in your materiality assessment, you may not have recognised a local water risk which hasn’t yet been linked to climate change, but which could affect your production line or supply chain.

Another example might be that your gender pay gap is not just poor, but comparatively worse than your competitors. You might consider it as a long-term issue that will self-rectify over time, due to recent HR policy changes in your company. However, if you find yourself expecting high numbers of retirements in the next few years, you will be struggling to attract the brightest and best candidates due to your perceived equal pay disparity.

You could be much more exposed to a tangible risk but not have recognised it as a result of not factoring for time, or imminence.

Second, if the materiality assessment is not compatible with how the business is managed (strategic goals, annual business planning, pay and rewards), in terms of responding to customer demand and other factors, it will never be truly integrated into decision-making processes.

If you spend months every year running a formal materiality assessment with multiple sets of stakeholders, which is out of sync with business planning and external reporting cycles, you won’t have achieved more than box ticking. Yet, the output of this (including the XY plot) features prominently in CSR reports, perhaps in the belief that “if everyone does it, it must be what people want to see”. This idea should be challenged constructively.

Materiality isn’t something you should think about once a year. It is something you should own and use to drive action to focus on what matters the most to your company. There is no right or wrong way to do this, but you should follow the approach taken by your finance or audit team and supplement it with guidance available on CSR issues. And don’t forget about time, even if you can’t draw a 3D plot on Excel.